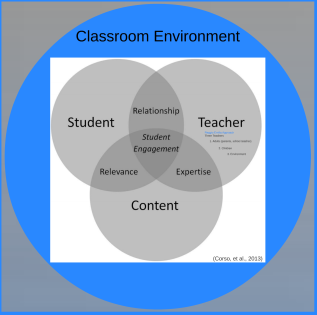

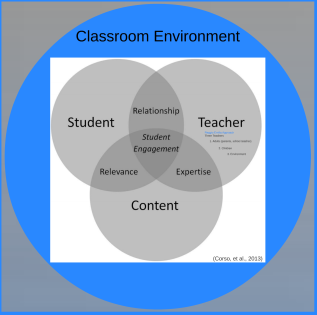

This spring I gave a talk at the Mountain Lake Symposium on the topic of classroom design. I thought I’d share a few practical ideas from that talk here, especially for music teachers who are dreaming up new ideas for the upcoming school year. I would venture to guess that many of us focus our curriculum planning and design attentions on three major elements: (1) the content area (music, instruments, songs, books), (2) teaching (approaches, techniques, methods), and (3) students (needs, interests, backgrounds). This makes sense, as these are three important and complex elements of our practice. In my post today, though, I want to focus on a missing element from this model, something so commonplace and visible, that it is rendered invisible—the classroom environment.

This was not something invisible to one of the pioneers of the Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education, Loris Malaguzzi. He argued that the classroom environment was so important to learning that it was the third teacher–after adults and children. Malaguzzi stressed the importance of constructing classrooms that act as agents in the educational process. When a classroom is functioning like a third teacher, it feels safe and welcoming to children, it is responsive to children’s curiosities and interests, and it furthers learning and encourages social engagement. The design of the classroom environment is an important (sometimes neglected) element of curriculum design that deserves our attention.

As you spend time this summer studying new music, constructing curriculum units, and planning field trips for your students, you might also think about the design (or re-design) of your music classroom to make it a “third teacher.” While some things are fixed, like walls and windows, many things are within your control. Think about your music classroom less as a fixed shell, designed to contain students in manageable learning environments, and more like a space that can be inviting, dynamic, and conducive to learning. It can be a place that sparks children’s wonder and curiosities about music. How could you make the metaphorical walls around your classroom more porous? How could you make furniture and objects serve the curriculum to further student learning? Here are a few (Reggio-inspired) guiding principles to consider as you think about re-designing your music classroom this fall.

photo credit: Andrew Kromholz

photo credit: Andrew Kromholz

AESTHETICS. The aesthetic of the classroom is more than bulletin boards and decorations. It is about the feelings that the music classroom conveys. Does it feel like an industrial space? A living room? A factory? A music production studio? Is there any place in the classroom that seems inviting enough that you would want to sit on the floor and listen to music or gather around to sing? A Reggio-inspired classroom is one that strives to make classrooms feel warm and inviting, much like a home. Think about what you do to make your home feel warm, inviting, and comfortable. How might you design your classroom with that in mind? A Reggio classroom might have soft home-like furniture, table lamps for warmer lighting, and attractive decorative elements. Decorations need not be childish or limited to those image/decorations that are designed specifically for classrooms (you know the classroom cut-out cartoonish figures I am talking about). What about an art print depicting music (Picasso’s Three Musicians) or better yet, children’s depictions of three musicians or pictures of students in musical trios? Think about bringing elements from nature in the space, including natural light, living plants, and natural materials such as wood and stone. Many classrooms, especially elementary classrooms, can become overly cluttered with ready-made school decorations, student work, charts, posters, materials, etc. which can be distracting and overwhelming to children. Remember the axiom adopted by modernist architect, Mies van der Rohe: “less is more.”

SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT. How does the classroom design encourage (or discourage) collaboration, interactions, and relationships among people? Chairs and working tables that are light and easily movable are ideal. How can you prepare the furniture you anticipate will be needed for a particular activity or project in the classroom such that students can learn from you and from each other? A fixed, teacher-always-at-the-center, layout of furniture is not always the most conducive to learning. The music classroom might be conceived of in zones, each with different functions. Think of the social functions of different zones in your home: (a) the reading nook–a zone for contemplation and individual musical experiences, like listening, (b) the large kitchen table–a zone for small group work, discussions, or experimentation, (c) the hearth–a zone for more intimate, informal gatherings for reading, chamber music, or group singing, (d) the backyard–a space for free play and experimentation. These are just a few of the many ideas you might dream up.

Even the things you choose to display on the walls, windows, and doors can lead to greater social engagement. For instance, walls which display school-ready holiday decorations, pictures of composers, or rhythmic note value charts usually do little to encourage conversations or questioning. They tell closed stories. Instead, you might choose to decorate walls with students’ music compositions, drawings inspired by listening experiences, or photographs of students engaged in learning or performance. These tell more open stories, inviting conversations with parents, other teachers, administrators, and/or students. They also make student learning and classroom engagements visible.

TRANSPARENCY. Speaking of the visible, one design principle of the Reggio classroom is transparency. That is, musical instruments and other materials and equipment for learning should not be stored out of sight, in a closet or an opaque storage bin. Instead, they should be displayed in transparent containers or on shelves so that children can see them. In sight, children are more apt to ask questions about them; teachers may be more apt to bring them out to use, study, or draw upon in a moment’s notice. A teacher might also choose to move an object to a prominent place, where children are bound to stumble upon it, examine it, and ask questions about it. You might sit a ceramic ocarina in a prominent place for children to notice as they come into the room. Moving an object into a prominent space to capture children’s attention is called a provocation. The idea is that the placement of an object sparks wonder, leads to questions, and allows for the curriculum to emerge from the child. How might students respond to seeing the inside of a piano at work? Transparency can be interpreted in numerous ways and inform classroom design decisions.

RE-IMAGINE. In a 2016 interview on On Being, Yo-Yo Ma compared performing to hosting guests at a dinner party–an act of hospitality. Its purpose, he said, “is that we’re communing together and we want this moment to be really special for all of us. Because otherwise, why bother to have come at all?” How might you design your music classroom differently if you were to think of it as your home, where you host guests (children, parents, other teachers) for a limited period of time? What metaphor best described the classroom environment you hope to create? I hope this blog posts sparks your creativity in re-thinking the space you call home during most of your waking hours. I’d love to see photos of your reimagined spaces for music learning.

werk will include a number of creative music projects for students. These projects will likely have guidelines that provide focus and structure to students’ creative efforts. Depending on the nature of the project and number of restrictions, the project will be more or less “open” (i.e., free).

werk will include a number of creative music projects for students. These projects will likely have guidelines that provide focus and structure to students’ creative efforts. Depending on the nature of the project and number of restrictions, the project will be more or less “open” (i.e., free).

photo credit: Andrew Kromholz

photo credit: Andrew Kromholz

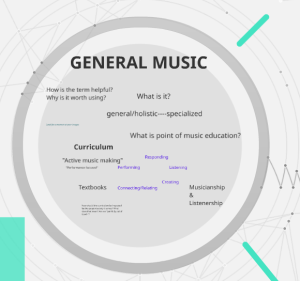

The general music teacher, by definition, is a brand of music educator who provides a learning environment for students to develop musical knowledge, skills, and understandings through a wide array of experiences—from performance to deep listening to composition to historical study of music. This is different from the generalist teacher (classroom teacher) who provides instruction in all subjects (sometimes including music) and does not specialize or necessarily have formal training in music. The general music teacher is typically afforded the freedom to construct a curriculum that is not restricted to any one form of music making and learning, or specific style and genre of music. This freedom and breadth can seem overwhelming, especially for the inexperienced general music teacher, but it also offers the potential for the development of students’ diverse musical intelligences, which can lead to more specialized forms of music instruction, if so needed or sought by students. The holistic approach applied by general music teachers is no less challenging, relevant, or important than the specialized approach applied by other music teachers (e.g., performance ensemble teachers or guitar teachers).

The general music teacher, by definition, is a brand of music educator who provides a learning environment for students to develop musical knowledge, skills, and understandings through a wide array of experiences—from performance to deep listening to composition to historical study of music. This is different from the generalist teacher (classroom teacher) who provides instruction in all subjects (sometimes including music) and does not specialize or necessarily have formal training in music. The general music teacher is typically afforded the freedom to construct a curriculum that is not restricted to any one form of music making and learning, or specific style and genre of music. This freedom and breadth can seem overwhelming, especially for the inexperienced general music teacher, but it also offers the potential for the development of students’ diverse musical intelligences, which can lead to more specialized forms of music instruction, if so needed or sought by students. The holistic approach applied by general music teachers is no less challenging, relevant, or important than the specialized approach applied by other music teachers (e.g., performance ensemble teachers or guitar teachers).